Makos 13a.

Thanks to Eli Chitrik

1- Identify yourself!

The Mishnah says that the shogeg, upon entering the city he chooses for asylum, needs to identify himself and advise the inhabitants that “I am a shogeg refugee“. If they show no interest in his status he does not need to remind them again. This is derived from a verse in the Torah.

We mentioned the Yerushalmi that derives from this law that a person who is, say, versed in one Mesechta and he meets people that believe he is knowledgeable in three Mesechtos, he must advise them of their error and humbly admit his limited knowledge!

This is brought down l’halacha in the Hago’os Maimonis.

2- Chazakos of Public Office

The Mishnah continues about the state of the Shogeg upon his release from the city of refuge (as a result of the death of the then presiding Kohen Gadol).

So he goes back to his family to live without fear of retribution from the goel hadom and tries to pick up the pieces of his life.

What if he had a position in his community prior to the accident that caused his exile? Suppose he was the local favorite Chazzan or Rosh Hakahal of his Shtetl; does he have a right to reclaim his position? What if someone else was appointed in his absence?

The Mishnah says that there are two opposing opinions whether or not he can indeed reclaim his original position.

This topic of a Chazakah of public office and if one inherits such a post from a father is rather wide and much has been written about it.

We scratched the surface by discussing a few basic sources on this topic.

Generally, there are a few references in Chumash that a son, if he can “fill his father’s position” is entitled to inherit the position. These references pertain to a King and a Kohen Gadol.

We find this concept of inheriting a position in areas of a different nature, (not monarchy or Kohen, but) positions such as a Rav or a Chazzan.

At first glance it seems from the above two references that all positions (King, Kohen, Rav, Rosh Yeshiva, Menahel etc.,) should have the same ruling, i.e., automatic yerusha to a fitting descendant.

The problem is that the Rashba was asked about a situation of a Chazzan and surprisingly he answers that “it depends on the Minhag”.

But if it is a Biblical directive then the Minhag should have no sway!

So we must say that there are two categories in public positions:

- One which follows the Torah directive of a son inheriting the position.

- One which is dependent on the individual community Minhag.

We find a few opinions on how to define and categorize the above two groups.

The Alter Rebbe (O”C 53, 33-34) writes that firstly in regards to a position of Torah – such as a chacham who is appointed to teach Torah or to be a judge there is no automatic inheritance for “Torah is not inherited”; It is free for anyone to take it. Thus, anyone capable of assuming the post has a right to the vacated position no less than a son. The community thus decides.

[Does the Alter Rebbe’s “Torah category” include a Rav, Dayan or Rosh Yeshiva? Please comment]

On the other hand

1) A non-Torah job such as a Chazzan, then his son, if he fits the position of course, come before other candidates.

2) Now if the Minhag is for the son NOT to inherit his father’s position then all candidates have an equal chance. And in such a case, where the Minhag was not for a son to automatically inherit the position, was the scenario the Rashba was referring to. But if there is no such Minhag then the community must adhere to the Torah principal of a son inheriting his father’s position.

In short the Alter Rebbe’s opinion is that with regard to inheritance:

- All positions (except a Torah one) must follow the Torah law.

- Where there is a Minhag not to follow it!

[Is this a case of Minhag mevatel Halacha?… Please comment]

The Chasam Sofer (O”C 12 ) has a different take on this. He also says that any Torah position is free for all to take. But his opinion is that:

- Any position of authority and communal obligation (like a king) falls into the Torah directive of a son inheriting the position, and

- This rule does not apply to any non-authoritative position such a Chazzan or Rav (who is a purely Torah figure with no authority or obligation…).

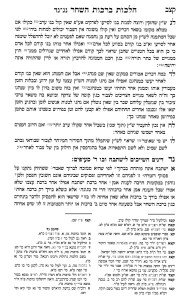

PDF: chasam sofer oc 12

Thus the Rashba, who was referring to a Chazzan, states that one should follow the Minhag and not follow the Torah directive.

We spoke about the story of Rebbi – Reb Yehuda Hanasi – who instructed that his son Reb Gamliel should inherit him as Nasi despite his other son Reb Shimon being a greater Talmud Chacham.

Yanki confirmed via Chazzan Kwartin in his famous piece on the Asara Harugei Malchus that it was in fact Reb Shimon the son of Reb Gamliel who was martyred.

The Tzemach Tzedek (OC 21) writes that the categories (and the reconciliation of the Torah instructive and the Rashba) of the Chasam Sofer are “dochuk“, meaning difficult to accept.

Interestingly, the Chasam Sofer, ten years after penning his first letter had second thoughts about the idea that a Rav has no community obligation. See here (13)

it would appear that the Alter Rebbe, in the end of Se’if 33 would include a Rav and Rosh Yeshiva in the category which is not inherited: he uses the expression:

“a chacham who is appointed to be marbitz torah, or to judge…”.

Why would a “chacham hamemuneh l’harbitz Torah…” be any different than a rav? And the words”to judge” refers to a Dayan, no? So then then we are talking about what we call a community Rav.