Makkos 19a (2)

Special Thanks to Alex Heppenheimer.

The Gemara mentions that a ger, when he brings bikkurim, can’t make the accompanying declaration (מקרא ביכורים), because he can’t say אשר נשבע ה’ לאבותינו. This in turn is based on a Mishnah in Bikkurim which says so (with the proviso that if his mother is Jewish, he can say it).

This turns out to be not so simple. There are actually two possible issues with a ger’s מקרא ביכורים: the lack of a portion in Eretz Yisrael, and that he’s not descended from אבותינו.

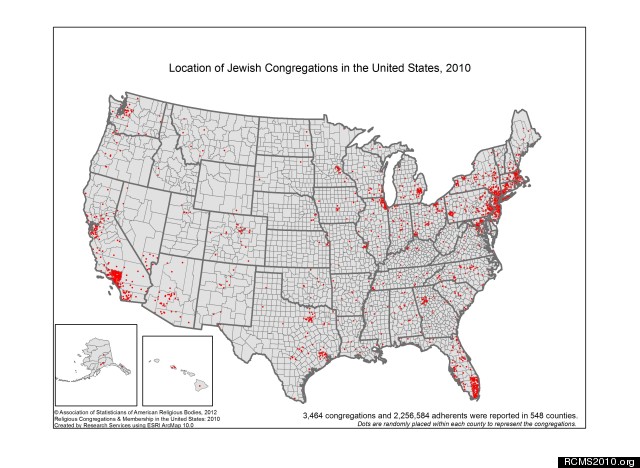

Now, there was indeed one group of gerim who did get a portion in Eretz Yisrael. בני קיני, the descendants of Yisro, were given a fertile area of 500 x 500 amos near Yericho to live in until the Beis Hamikdash would be built (at which time it would be given to whatever shevet provided the equivalent area for the Har Habayis).

(Incidentally, they didn’t stay there for long; they needed a rebbe, and so they wound up leaving this area and traveling to Arad, in a desolate part of the Negev, to study under Osniel ben Kenaz. Their reward was that some of their descendants served in the Sanhedrin.)

So the Yerushalmi mentions בני קיני, and then goes on to quote a baraisa that R. Yehudah holds that a ger can recite מקרא ביכורים because Avraham is the father of all nations, and a psak by R. Abbahu that the halachah is like R. Yehudah.

Tosafos (in Bava Basra) discusses what this means. According to Rabbeinu Tam, the Mishnah (R. Meir) is saying that any kind of ger (בני קיני or anyone else) can say מקרא ביכורים as long as his mother is a born Jew, while R. Yehudah holds that you need to be בני קיני as well as אמו מישראל. (Although he asks: how does a ger say ארמי אובד אבי וגו’, which seemingly refers to Yaakov?)  Ri understands that there’s no real machlokes between R. Meir and R. Yehudah – both agree that only בני קיני who are also אמו מישראל can bring bikkurim and say the pesukim.

Ri understands that there’s no real machlokes between R. Meir and R. Yehudah – both agree that only בני קיני who are also אמו מישראל can bring bikkurim and say the pesukim.

On the other hand, Rambam states that any ger (no distinction whether אמו מישראל) can say מקרא ביכורים, because he understands R. Yehudah to be saying that אב המון גוים makes it possible even for a ger to say לאבותינו. He also adds a detail: “the promise was first given to Avraham that his children would inherit the land.” Now, what does that mean? Also, why then does the Rambam differentiate between מקרא ביכורים and וידוי מעשר – the latter, he says, a ger can’t say? (The question is actually on the Mishnah and the Yerushalmi – no variant opinion is given about וידוי מעשר.)

Ramban explains that in theory gerim could have been בני ירושה because of Avraham, but practically speaking they didn’t get a portion simply because Eretz Yisrael was divided only among those who left Egypt. But just as those who were children at יציאת מצרים didn’t get a portion of their own but yet, when they do eventually inherit, can say מקרא ביכורים, so it is with gerim – they are essentially בני נחלה. (As for Rabbeinu Tam’s question about ארמי אובד אבי, Ramban answers that once the ger is considered a descendant of Avraham, then by extension he has the same relationship to the other Avos.)

Kesef Mishneh takes a different tack. When Hashem promised the land to Avraham he wasn’t yet אב לגרים – that came only afterwards, and by that time his biological children were entitled to it. But it’s not that intrinsically gerim can’t inherit Eretz Yisrael.

Shaagas Aryeh, in the course of a long teshuvah about milah for בני קטורה (they are obligated – Rambam, Hil. Melachim 10:8), discusses the idea that the Rambam’s point about the promise to Avraham is that even though Yitzchak and Yaakov aren’t called “fathers” of gerim, since Avraham is, that’s good enough. (Which means, he says, that Rambam would necessarily disagree with Ramban’s answer about ארמי אובד אבי. One of the other mefarshim on Rambam suggests that maybe he would understand that posuk as Rashbam does, “My father (Avraham) was a wandering Aramean.”)

Incidentally, he points out that בני קיני are in fact biologically descended from Avraham (since Midian was one of the sons of Keturah); but because of כי ביצחק יקרא לך זרע,

they’re excluded (which is why R. Meir says that there needs to be אמו מישראל to be able to recite מקרא ביכורים). Also incidentally, he points out why in Nedarim (recent Daf Yomi) we are told that even circumcised בני קטורה are considered uncircumcised – because while they are obligated in milah, they don’t have the mitzvah of periah, and מל ולא פרע כאילו לא מל.

As for the difference between מקרא ביכורים and וידוי מעשר, there are several explanations, most of which focus on the difference in wording between the two.

Radvaz notes that by מקרא ביכורים the expression is אשר נשבעת לאבותינו לתת לנו, which can be understood as נשבעת לאבותינו – to Avraham – and therefore לתת לנו, it pertains to the whole Jewish people, gerim included. Whereas by וידוי מעשר the expression is אשר נתת לנו, and it wasn’t given to the gerim; כאשר נשבעת לאבותינו there refers to זבת חלב ודבש.

Mishneh Lamelech quotes R. Moshe ibn Chaviv, who points out that Yechezkel states that gerim will get a portion in Eretz Yisrael in Moshiach’s times; therefore they can well say לתת לנו in future tense. (A logical reason for this is that gerim who joined the Jewish people after Yetzias Mitzrayim, when we were at the highest heights, may not have been totally sincere; not so with those who became gerim during the years of galus.) Whereas אשר נתת לנו is in past tense.

A couple of mefarshim on Rambam bring an idea from R. Shmuel Primo,  that the expression ארץ זבת חלב ודבש is never found in Chumash Bereishis (addressed to the Avos), only in Shemos (addressed to the Jews in Egypt) and afterwards. So if in וידוי מעשר the expression כאשר נשבעת לאבותינו refers to ארץ זבת חלב ודבש, then אבותינו there necessarily means the Jews who were in Egypt – and the ger isn’t descended from them.

that the expression ארץ זבת חלב ודבש is never found in Chumash Bereishis (addressed to the Avos), only in Shemos (addressed to the Jews in Egypt) and afterwards. So if in וידוי מעשר the expression כאשר נשבעת לאבותינו refers to ארץ זבת חלב ודבש, then אבותינו there necessarily means the Jews who were in Egypt – and the ger isn’t descended from them.

(This R. Shmuel Primo – probably no relation of the hatter – was an interesting character. He was a youngish talmid chacham when Shabsai Tzvi appeared on the scene, and he became his secretary – and even after Shabsai Tzvi’s shmad he continued to believe in him. He later became rav of one of the important communities in Turkey, wrote a couple of sefarim, and is quoted respectfully by the Chida and others.)

Yet another answer, from Mirkeves Hamishneh, is that מקרא ביכורים must be said in lashon hakodesh, and there אבותינו can mean “masters” (as in וישימני לאב לפרעה); whereas וידוי מעשר can be said in any language, and in other languages “av” means only “father.”

*

All of this, in turn, brings up the question about what a ger says in davening. Can he say אלקי אבותינו, and can he say in bentching שהנחלת לאבותינו?

The Mishnah there in Bikkurim says that a ger should say אלקי אבות ישראל, and in shul he should say אלקי אבותיכם (unless אמו מישראל, in which case he can say אבותינו because of her). On the other hand, we have the opinion of R. Yehudah mentioned earlier, and the Yerushalmi stating that R. Abbahu paskened like R. Yehudah (which necessarily would have to refer to davening, since in R. Abbahu’s times there were no bikkurim).

In the Tosafos mentioned above, Rabbeinu Tam decides according to the Mishnah, and therefore says that a ger can’t lead a mezuman, because he can’t say על שהנחלת לאבותינו. Whereas Ri argues that the halachah is like R. Yehudah, and therefore that he can.

Similarly, Mordechai tells how in Wurzburg they prevented a ger from being chazzan because of the problem with him saying אלקי אבותינו, but that Rabbeinu Yoel allowed it based on R. Yehudah.

Yossele Rosenblatt (not a ger)

Rambam, too, writes in a teshuvah to R. Ovadiah the ger that he should daven like everyone else, because all gerim are children of Avraham.

So this is accepted as halachah. The Alter Rebbe summarizes it as follows: with women there is a safek whether they are chayav in ברכת המזון מדאורייתא, since they don’t get a portion in Eretz Yisrael (and they are עם בפני עצמן, so not necessarily included with the men). With Kohanim and Levi’im, the only reason they are chayav is because they have ערי מקלט, but otherwise they are important enough to have a status of their own. Whereas gerim can be considered an appendage (נטפל) to the Jewish people.

One last detail we talked about: isn’t being a chazzan a type of שררה, and gerim are not allowed that? The answer is that a chazzan is not telling anyone what to do, just saying kaddish and Borchu and so forth, to which everyone answers.